Content warning: This post discusses an incident of violent terrorism that resulted in death.

Meghan Zipin was running the Boston Marathon for a second time, and loving every second of it.

“There are sometimes those days that are just so perfect, the weather’s perfect, the sun is perfect, the wind is perfect, and April 15, 2013, was one of those days,” she tells POPSUGAR.

There’s a clock tower in the S.S. Pierce building around mile 24 of the course. Despite having her running watch on her wrist, when Zipin passed the clock, she studied the time and realized that she might be able to run a sub-four-hour marathon, “which would’ve been a real accomplishment for me,” she says. “I remember seeing that clock and changing my pace.”

Closer to the finish, she passed two friends who were cheering her on. They blew her kisses, and yelled that they were running to the finish line to meet her there. As Zipin finally reached the 26.2-mile mark and her first foot hit the finish line, the first of two bombs exploded in what’s now known as a terrorist attack.

Zipin’s life was forever changed by that day. Luckily, she escaped largely unscathed, as did her husband — who was near the finish line but, by chance, decided go around the block to avoid the crowd — but her two friends suffered life-threatening injuries. In total, more than 260 other people were injured in the bombing, and three lost their lives.

Like most people who’ve lived through traumatic events, Zipin’s recollection of the event is peppered with “what ifs”: “What if I didn’t see the clock? What if I stopped and went to the bathroom or didn’t see the girls? All these things change what happens in your life. They seem insignificant but have a bigger impact.”

She’s come out stronger on the other side, but the journey to healing hasn’t been easy or linear. On April 15, the 10th anniversary of the Boston Marathon bombing, Zipin is releasing a book of poetry, “First Light”, which explores the aftermath of that day in Boston, including her life with PTSD and survivor’s guilt, and how the bombing has affected her relationships and experience with motherhood. Her hope is that “someone can pick it up having experienced something really hard and read the words and say, ‘Oh my god, that’s what I felt too,’ or ‘That is what panic is like.’ I want someone to read it and say, ‘Me too.'”

On the near-10th anniversary of the bombing and just head ahead of her book release, I talked with Zipin to learn more about her story: how her relationship with running changed, the tools she’s used to heal, and the positive lessons that came out of it all.

POPSUGAR: What was your healing journey like after the bombing?

Meghan Zipin: The year afterward was, and still is, a haze for me. I have concrete memories and then a lot of in-between space. I think my body was trying to protect me at that time from everything that I had experienced and seen, not just at the bombing, but everything that followed, too.

Then, as time went on, I started working with therapists and doing yoga. I started going to yoga classes with really small goals, like trying to listen the whole time or trying to pay attention. Nothing to do with the practice itself. Slowly, as I became more familiar with the language of yoga and found classes that were more like power yoga — that got my heart rate going in the way that running did — I kind of fell in love with it.

I’m a trained physical therapist, and over the last 10 years, I ended up becoming a yoga therapist. I use my PT background to help keep people safe, but we use yoga as a modality to move through something physical or emotional. And I’m able to accompany people on that, and that is an amazing gift that’s come from this.

PS: You mentioned you were seeing therapists and that you had PTSD after the bombing. What was it like trying to work through that?

MZ: I don’t think I even said the term “PTSD” until after the trial in 2015 or maybe right before it. I would not accept that this had taken hold of me. Hindsight being what it is, if someone had said, “You know, it’s okay to not be okay,” that probably would have been a really powerful moment for me.

I always describe PTSD as a really sneaky beast. Right after the bombing, I was afraid to walk down the sidewalk because I thought the sidewalk was going to explode because at one point it did. And now I had this history in my mind and body that said, “Oh no, sidewalks can explode.” It took a lot of work personally and with some really great therapists to recognize that what happened was abnormal but that my response to it is actually normal. What happened was crazy and your body is just trying to help you survive.

Still, panic can sometimes come on for reasons that I don’t even know. Maybe something makes my heart rate go up and the panic is triggered physically, or I open the oven and there’s a wave of heat. You don’t think anything about that, but there was a massive wave of heat when those bombs went off. It’s these little things that can set off the fight or flight or freeze response in your body. I feel like I still get tricked and it’s 10 years later.

PS: What has your relationship running been like since that day?

MZ: Eventually, I did stop running. I ran the marathon in 2014 because I really thought I was capable of reclaiming what I felt was stolen from me and from so many people. And that was a definite falsehood; it was a panic-inducing experience.

Right after the bombing, I was afraid to walk down the sidewalk because I thought the sidewalk was going to explode because at one point it did.

I did fine up until the 20-something-mile mark when I saw the clock. I had such a visceral memory of making a decision to change my pace at that time, that from that point forward, I slowed way down. There were something like four miles left from that point, but it probably took me the equivalent time of 10 miles because I was just afraid, like: “That happened last time, why wouldn’t it happen again this time?”

Even as I finished, my body was overwhelmingly sad. I also felt a little bit of an expectation, to be honest, that I was going to reclaim something. People were rooting for me. They were like, “You can do this.” Yet I had a sense of, “Oh, shit. I can’t do this,” and that it wasn’t the right choice for me. But I didn’t have anybody in my life at that time that I would listen to or that was willing to say, “No, you can’t,” or “No, you shouldn’t”. Everyone wants to believe that you can reclaim what was taken from you, but what was taken wasn’t a tangible item. And I think that’s what I was looking for that day.

So I don’t feel like I stopped running as a choice; it was more of a feeling that I couldn’t do it anymore. I ran one other marathon after Boston in 2014. It was a race called Grandma’s Marathon in Duluth, Minnesota, and my husband and I didn’t tell anybody. I didn’t want anyone cheering for me, I didn’t want the messages of “good luck” or “you’re brave”. I just wanted to go and do it for myself. He and I flew out there, and he didn’t even come to the course, he just met me at the finish line. I ran a sub-four-hour marathon, which is just what I wanted, simply so I knew I could do it. (I ended up finishing Boston 2013 in just over four hours. Despite the bomb going off at the same moment, my foot did get timestamped on the finish line.)

That race in Minnesota was the last time I ran. Running just wasn’t the meditative, joyful thing that it used to be for me.

Something really amazing that the Boston Athletic Association has done since the bombing is that for members of the One Fund, which is basically the folks who survived the marathon bombing, every year, they offer us a bib with our number that we can either run with ourself or gift to someone we know who otherwise maybe wouldn’t qualify, because it’s such a strict standard, and they don’t have to fundraise. I’ve had five really awesome, powerful women in my life run the marathon with my number over the last 10 years. That’s been a real gift because the Boston Marathon is one of the best experiences of my life, and to be able to gift that to other people has been something I’ve loved.

PS: Do you feel like yoga filled that spot running used to occupy in your life?

MZ: That’s a really good question. The preface of my book is actually the victim impact statement that I read in the courtroom to the bomber. And one of the things I said was that I will always miss that runner girl because she’s one of the ones [that’s gone]. And if I started running today, I’m a totally different person. I’m in the same body, but my worldview, my experience in the world, it’s just not the same.

I don’t feel like I stopped running as a choice; it was more of a feeling that I couldn’t do it anymore.

So to say that yoga is filling that slot, I can’t say for sure. But yoga offers me a place to put energy, it offers me the opportunity to sometimes slow down, which can be helpful, and sometimes practice tolerating things that are uncomfortable.

I think that yoga meets you where you’re at in a way that running doesn’t. I used to tell people that running is really hard until it’s not, and then it can be awesome. And yoga is kind of different every day and it can meet you where you’re at every day.

PS: In your courtroom impact statement, you also said “I know one day I’ll be a better mother and my husband a better father because we will show our children all that is good in this world; all there is to be thankful for.” Now that you have three young kids (ages 5, 4, and 1), how has this experience shaped motherhood for you?

MZ: I said that in the courtroom because somewhere in the depths of despair, I feel like my body and my heart had that belief that there would still be some good that would come from this. And I think it has shaped us as parents in the sense that we don’t sweat the small things. Our house is messy. My children run in the mud and they paint like Jackson Pollock and they experience the world.

I want them to experience the world, my husband wants them to experience the world, and we allow them the freedom to do that. And I’m not sure that we would have been . . . We probably would’ve placed some more limitations and been a bit more uncomfortable with letting them kind of be wild and free. But that’s the thing that seems to be bringing them joy, and that’s our focus. We tell them their job is to be kind. Their job is to play. I hope one day when they have a bigger understanding of the world and a greater understanding of where their family of origin came from, I hope that’s something they reflect on with gratitude.

PS: How did you end up turning to poetry to cope?

MZ: Well, I didn’t. I turned to my phone. One of the really early manifestations of panic, anxiety, and ultimately PTSD for me was insomnia. At night, when I wasn’t sleeping and the world was quiet, I would make notes in my phone. Sometimes it would be something really sad or grief-ridden or guilty. And sometimes it would just be that I noticed a heart rock on the street that day.

So I had this really big repository of notes from that time. I love poetry and I’ve always written it, so a couple of years ago I started taking those notes and using them as poetry prompts. Having a little bit more distance from the experience, I could look at something like the time I was in the courtroom or my thoughts on what grief feels like and I could write about it without pouring over onto the floor.

PS: Were you ever nervous about publishing this and letting other people see these thoughts from such a dark time in your life?

MZ: Yes, and I continue to feel that. This is a really personal story, and I think we all, especially as women — and maybe as mothers, because kids demand a degree of presence that few other things in life do — we’re able to look OK and mask our way through the world. And when you have an invisible injury, whether you’re a veteran or someone who’s experienced something terrible and PTSD is a part of your life, you might not “look the part” or like there’s something wrong.

I had a lot of anxiety about sharing the book with my parents. I knew they understood things were hard but likely not to this degree. Also with my friends that were injured the day of the race. But the overriding feeling for me is of offering a hand to someone else who I don’t know but who needs one. I’ve read a lot of memoirs in the last 10 years, and anytime I can find that inkling of connection, it helps me take a little bit of a deeper breath. I’m not so broken or I’m not as broken as I thought I was because that person is doing OK and they had something really big happen in their life, too.

Reflecting on this experience and putting my thoughts together into this book wasn’t easy. But it helps to have my three boys now, being able to write a bit about them and the way that they see the world. To them, I’m only mama. This is the only version of me they’ve ever known. They are such joyful children, it feels like a privilege to watch them grow. It feels like a privilege when one of them will pick out the prism in a bubble. Like, oh, you see a rainbow. Of course, you do.

If I cut to eight years ago or seven years ago, there was a time when I didn’t think that my marriage would survive. There were times when I didn’t know if I would be able to continue living in this body in the way that it felt. And to now be, like going to my kids’ art show tonight at their school, and to be here and doing those simple things is just, it’s kind of wild.

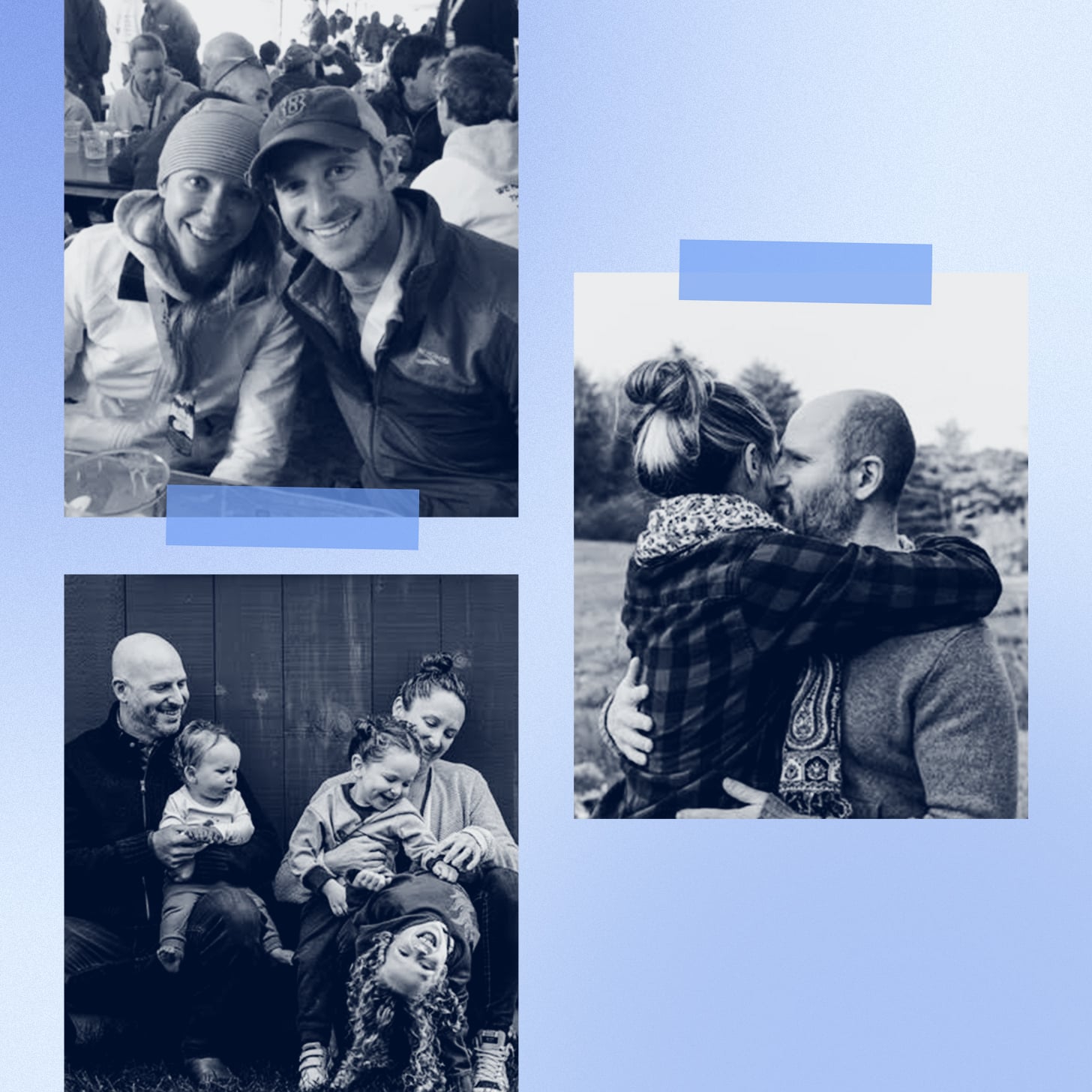

Image Sources: Images courtesy of Meghan Zipin and Photo illustration: Aly Lim

Thanks for sharing your knowledge on this topic. It’s much appreciated.

This is a topic I’ve been curious about. Thanks for the detailed information.